Hydra

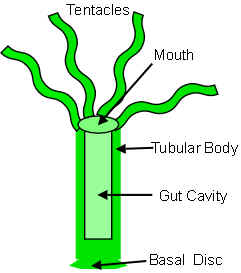

Hydra are truly fascinating small aquatic animals. Most hydra are tiny, reaching a maximum of only about 30 mm long when fully extended. They are barely visible to the naked eye and a hand lens or microscope are needed to be able to see them properly. When the body is extended with the tentacles waving in the water, they resemble a small piece of string which has become frayed at one end. If disturbed, a hydra will contract its body and tentacles, so that it now resembles a small 'blob'. They can be found in freshwater ponds and slow-moving rivers, where they usually attach themselves to submerged plants or rocks. The hydra pictured above came from pond water which contained large quantities of filamentous algae (a very simple kind of plant). There are four species of *Hydra in Britain. They range in colour from green, through varying shades of brown. The green hydra above (Chlorohydra viridissima) gets its colour from green algae which live inside its tissues in a mutually beneficial relationship. The algae living inside the hydra benefit from having a sheltered safe environment and obtain food by-products from the hydra. The hydra also benefit from algal products. It has been shown that hydra which are kept in the light, but otherwise starved, survive better than hydras without any green algae inside them. They are also able to survive in water with a low dissolved oxygen concentration because the algae supply them with oxygen. This oxygen is a by product of the photosynthesis carried out by the algae. Green hydra transmit the algae from one generation to the next in the eggs.

Hydras move their bodies about in the water while they are attached, extending and contracting by a mixture of muscle movement and water (hydraulic) pressure. This hydraulic pressure is created inside their digestive cavity. The cells lining the digestive cavity have little flagellae (minute hair-like structures) on their surface. By beating these flagellae like miniature oars, currents can be created which draw water into the digestive cavity. This raises the water pressure inside, which causes the hydra's body to increase in length. The body of a single hydra can change from being 20mm long when it is relaxed and extended, to being as little 0.5mm long when it has contracted (using muscular movement) after being disturbed. Hydra are not always attached to the substrate and can move from one spot to another, either by gliding along on the basal disc or by somersaulting along. When somersaulting, they detach the basal disc and then bend over and place the tentacles down on the substrate. This is followed by reattaching the basal disc further along, before repeating the whole process again. They may also float about in the water upside down. When they are floating, it is because the basal disc produces a gas bubble which carries the animal up to the water surface. The single-celled algae (Chlorella) which give Chlorohydra its green colour, live inside the cells lining the digestive cavity. Interestingly, these algae can also be found living freely outside of hydras. One side of tree trunks (often the north side) in woods is sometimes covered in a smooth green coating almost as if it has been painted. This green covering usually advertises the presence of a whole mass of free-living Chlorella algae (although other species of green algae will also grow on tree trunks).

Hydra are carnivorous and feed mainly on small

crustaceans like water fleas (Daphnia) and small worms. Although hydra are fairly simple animals, the stinging

cells which they use to catch their prey are quite complex structures. This toxin is too weak to have any effect on humans which happen to touch the tentacles, unlike the toxins from the stinging cells of jellyfish, which can cause painful stings to humans. (Jellyfish are also closely related to Hydra.) Once the prey has been paralysed, the tentacles will pull it towards the mouth, where it will be swallowed to be digested in the digestive cavity. Much of the digestion is accomplished by enzymes secreted into the cavity. This means that hydra can eat relatively large prey in comparison to their size. Small particles resulting from digestion are then engulfed by the cells lining the digestive cavity. In catching prey, hydra use up a lot of their nematocysts, which can only be discharged once. A study was carried out on one species of Hydra which showed that 25% of the nematocysts on the tentacles were used up in the process of catching and eating one brine shrimp. It took about 48 hours for new nematocysts to be produced to replace the used up ones.

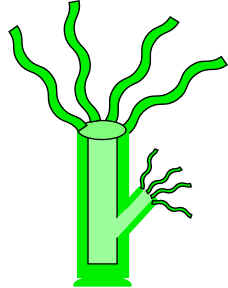

As it begins to get colder, sexual reproduction may start to take over. Most Hydra species have individuals which are either male or female. Eggs are produced in the outer body wall of female hydra and are fertilised by sperm released into the water by neighbouring male hydras. Some species of Hydra are hermaphrodite, with each individual having both male and female reproductive organs. The seasonal timing of sexual reproduction is a way of helping the species survive over the winter. This is because the fertilised eggs have a tough shell or covering and can form a resting stage over cold periods. In the spring, the shell softens and a new hydra will emerge.

*Species of Hydra found in Britain Chlorohydra viridissima - Green Hydra Hydra oligactis - Brown Hydra. This species has a slender portion or 'foot' at the base of the body. Hydra attenuata - Slender Hydra. This species is also brown, but has no foot. Cordylophora lacustris

|